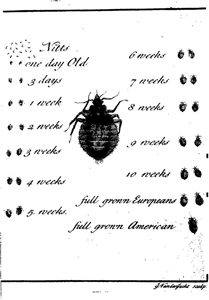

“Frontispiece, John Southall’s “A Treatise on Buggs,” 1730.” The author recently posted this on her Facebook page as one of many vermin-related pieces of history.

Editor’s Note: Dr. Sarasohn is a historian who is currently writing a book titled Getting Under Our Skin: A Cultural History of Vermin. She also maintains a Facebook page that covers how rats, fleas, bed bugs and lice affect the relationship between human beings — from earlier ages through today. Learn more at Facebook.com/lehnstul.

Vermin have always signified something deeper than a bite. In the Middle Ages, they provided “dermatological evidence” that God punished sinners. Alternatively, the lice- and flea-infested hairshirts of some saints imitated the sufferings of Christ.

Centuries later, moralists argued that God used vermin to encourage cleanliness. Socially, village life was enlivened by the practice of mutual delousing – a way to keep fingers busy during nightly story times, and to consolidate community ties. Vermin crawled through upper-class thinking; noble ladies prized their lice combs while poets envied the freedom of fleas to explore beneath the dresses of maidens. The poet John Donne famously sought to seduce a young woman by arguing their blood had already joined in a flea.

It’s not that anyone – except perhaps saints – especially liked hosting vermin. Early modern home-keeping manuals prized recipes for killing parasites, ranging from the dangerous (sulfur and turpentine) to the peculiar (roasted and ground dead cat). Upper-class men shaved their heads – and ladies their private parts – and donned wigs to reduce their lice vulnerability.

In the eighteenth century, vermin became a social yardstick, displaying one’s class, nationality and moral superiority. The upper classes embraced baths and clean underwear. As the middle class defined itself by manners and purity, beggars, gypsies and shopkeepers were condemned as harboring vermin; experts arose to battle bed bugs and lice.

The first professional exterminator advertised his services in 1730, promising an elixir to kill bed bugs, “that Nauseous Venomous Insect,” and received the patronage of the president of the Royal Society. He died a wealthy man. But fleas and lice, roving from body to body across class lines, continued to defy those who tried to control them, from exterminators to scientists. They demonstrated the porousness of the boundaries between people and groups, and how easy it was to get under the skin.

Fear of vermin merged with fear of slaves and foreigners, who were perceived as “low” creatures that could yet torment their supposed betters. In the play Les Miserables, convicts in a chain gang pick the vermin off their bodies and shoot them at the gaping bystanders through straws. Vermin could humble the powerful, at least momentarily.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, discoveries that vermin carried typhus, bubonic plague and other diseases intensified the campaigns against those considered verminous. Just as epidemiologists produced vaccines to prevent these diseases or medicines to cure them, others blamed internal enemies or foreigners for carrying the infection. When Reichsfüher Heinrich Himmler identified lice with Jews, he echoed an equally unfounded, prejudiced association of Jews with plague going back to the Black Death in 1345. Likewise, when the chief of the U.S. Chemical Warfare Service proclaimed after World War II that “the fundamental principles of poisoning Japanese, insects, rats, bacteria and cancer are essentially the same,” he was crossing the same hateful line.

Vermin don’t just scar our skin. They’ve also shaped society’s outlook.

For more information, a link to a 1730 newspaper ad of another professional pest controller that was specialized in bed bugs control:

https://desinsectador.com/2014/01/30/a-certain-remedy-against-buggs-by-john-williams-1733/

This is very cool, Carlos — thanks for sharing! —The Eds.