The threat of the deer tick (Ixodes spp.) has grown along with their hosts of choice. Photo: istock.com/Goldfinch4ever

Powassan can neither be detected with a test nor treated with antibiotics, but in severe cases, it has a 10 percent mortality rate.

The constant and almost unseen threat of the deer tick (Ixodes spp.) has grown along with their hosts of choice, white-tailed deer and white-footed mouse populations. A recent study by a group of researchers in Connecticut counted a higher number of ticks following winters with heavy snow cover, says Dr. Rick Ostfeld, an ecologist who has been studying ticks for two decades at the Cary Institute for Ecosystem Studies, Millbrook, N.Y.

“We know snow insulates, so it makes sense it would be protective for ticks,” he says.

Powassan (POW) is a fairly new and particularly threatening virus, which can show symptoms like headaches, nausea, vomiting, muscle weakness, memory loss and speech difficulty within two to three hours of a person being bitten by an infected tick. In severe cases, it can cause life-threatening inflammation of the spine and brain, resulting in death in about

10 percent of cases.

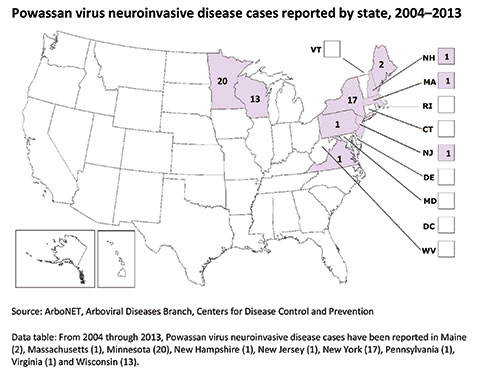

On the other hand, it’s also rare, having been diagnosed less than 50 times since 2005. First discovered in 1958, the virus was named after the city in Ontario where it was found in a young boy who eventually died from it. It is not considered to be transmissible from human to human.

Lyme disease and babesiosis, another recently seen and potentially fatal tick-borne illness with malaria-like symptoms, can be detected with a test and treated with antibiotics. The POW virus cannot, and managing symptoms with supportive care is the only treatment, so children are at particular risk because they’re among the most vulnerable and, potentially, most exposed to deer ticks.

Precautions that minimize risk include limiting skin exposure, using over-the-counter insect repellents, and avoiding areas where tick infestations most frequently occur.

Time is of the essence in preventing tick attachment and disease risk, says Dr. Richard Pollack, an entomologist at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston.

“A daily check can prevent this, so everyone in the family should be like little chimpanzees and look for them,” Pollack adds.

Four-legged family members should not be overlooked, either. Dogs are particularly good at picking up ticks.

Lyme disease-infected ticks aren’t just in forests and fields, says Dr. Ralph Garruto, head of the head of the tick-borne disease program at New York’s Binghamton University.

“We’re finding plenty of infected ticks in built environments, places such as city parks, playgrounds, work campuses and college campuses,” he says. “When people don’t perceive of these environments as risky, it makes the problem worse.”

Mark Negron is director of marketing and sustainability for Environmental Health Services, Norwood, Mass. Contact him at mnegron@ehspest.com.

Leave A Comment