- Osborne on Christmas Day, 2003. Photo: Osborne Pest Management

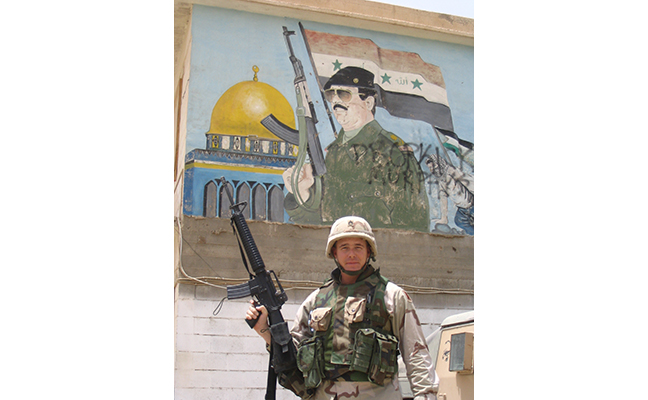

- Osborne in Abu Ghraib, circa 2004 Photo: Osborne Pest Management

- “Camel spiders” (Solifugae) are a common sight in Iraq. Photo: Osborne Pest Management

- A member of the 12th Medical Detachment identifying mosquitoes and sand flies. Photo: Osborne Pest Management

- Water was everywhere, despite the desert climate. Photo: Osborne Pest Management

- Osborne on patrol on Christmas Day 2003. Photo: Osborne Pest Management

- These days, Osborne runs his firm from Colorado Springs, Colo. Photo: Osborne Pest Management

- 12th Medical Detachment; the Fire Team and Patrol, part of the 2nd Battalion 156th Infantry when it was assigned to the 10th Mountain Division for the election mission. Osborne is second from left, holding the AK-47. Photo: Osborne Pest Management

- Osborne, circa 2004, trapping mosquitoes. Photo: Osborne Pest Management

- A member of the 12th Medical Detachment identifying mosquitoes and sand flies. Photo: Osborne Pest Management

Charles Osborne, ACE, president of Osborne Pest Management, Colorado Springs, Colo., has the unusual perspective of having treated for mosquitoes while serving in the military. Osborne, 52, joined the Army right out of high school and served in the first Gulf War. After he was honorably discharged and back stateside, Osborne did an internship with the Colorado Division of Wildlife. He then worked for a couple of local wildlife and pest control companies, but duty called once again: He was called back into active duty. He was assigned to the First Calvary Division, which was headquartered at Camp Victory, the largest military base since the Vietnam era.

His Division’s mission was to help train Iraqi soldiers, but Osborne would often pass the Preventative Medicine Unit 12 detachment, from Beloit, Wis.

“It was a small group, but a great bunch of folks,” he recalls, pinpointing the time as around late 2004. “They were health inspectors, and I helped them test the water during my time off. I was able to help them based on my pest control knowledge, to help control mosquitos, sand flies and rodents. I told them I had a Colorado pest control license and that I could help when I wasn’t on a mission,” he recalls. “Their colonel talked to my colonel, and that’s how I got back to work.

“It was something I wanted to do to keep my mind occupied and keep working,” adds Osborne, who studied natural resource and wildlife management during his service.

At their base, Camp Victory in Iraq, treatment areas included around structures, canals, surrounding foliage, and destroyed open sewer yards and systems.

“I developed a plan of treatment for an existing problem, where previous treatment had proved ineffective,” explains Osborne. “I decided to initiate a trapping and identification protocol prior to any treatment being made. After proper identification was made, a variety of methods were employed to control the mosquito population, which included cutting the reeds below the surface of the water and applying larvicide along the edges of the waterline and spraying a monomolecular film (MMF) on the surface of the water.”

Osborne reports that this strategy was successful, particularly in the canal areas. Other areas were sprayed or misted, as appropriate with an adulticide and insect growth regulator (IGR).

“Sampling and monitoring were performed on a regular basis to ensure efficacy, and treatments were modified as needed,” he says.

The area where Camp Victory was situated was comprised of several clusters, some of which were former palaces of Saddam Hussain. The canal system had long been inactive, and even blown up in some places. In other words, it was the perfect storm for mosquitoes: standing water and warm temperatures.

Photo: Dept. Medical Entomology

“The canal system was still a living system. There were reeds growing up through it, becoming stagnant. There were a lot of Coquillettidia and Mansonia mosquitoes present,” Osborne explains, noting that both species are known for attaching themselves to the reeds and breathing through the plant, snorkel-like, with their siphon tubes. “They were really concerned with malaria, but that wasn’t a big issue. The mosquitoes were more of a nuisance than anything else. If you went among the reeds along the canal, you were bound to stir up a flurry of mosquitoes.”

The previous strategy was simply to fog with a truck, which in Osborne’s opinion was going too fast to do any good anyway. He knew they needed to start with identification — trapping so they could get a representative sample.

“So when we trapped and busted out the book to get the ID process, I said this might be the problem: The mosquito larvae are attaching to the reeds and thriving,” he says. “The vegetation was too dense for what they were doing to be successful.”

Osborne suggested using third-country national (TCN) workers to cut the reeds below the water level, so any applied materials could get the chance to work. They began to see some success — until the workers refused to go in because the canals were rife with cobras.

Osborne and his colleagues turned to Plan B: The field needed to dry up.

“I said we need to drain, or at least divert the water. The area was too large to use the backpack granulars,” he recalls.

Osborne says he met a lot of great people during his time in the service, and ended the interview with a laugh about another branch of the military.

“We worked in small groups,” he says. “I was with a Navy Corpsman (combat medic) down by a canal, and suddenly, Suddenly, I couldn’t see him. I passed by (an outdoor restroom facility) and assumed he went there, though I was a little surprised he didn’t let me know he left. Then I realized he was knelt down right next to me. His naval camouflage was so good that I completely missed him among the reeds.”

Leave A Comment