Four PMPs share how they make bird management profitable year after year.

When you’ve built your business to the point where it consistently exceeds expectations in general pest and termites, it’s only natural to want to build on that success. Many pest management professionals (PMPs) see bird control as the next logical step — and become quickly discouraged when they cannot make it as profitable as their other segments.

But bird control is, forgive the pun, a horse of a different feather than other pest control segments. There’s the equipment investment, the training, the different expectations you have to give customers looking for an elimination of their problem — and the tasks put on them to make sure the problem can be permanently solved.

Read on for advice from PMPs in the field.

Bruce Carter: Roll up your sleeves

Bruce Carter, president of Farmington, N.M.-based Carter Services, has been in the pest management industry for 39 years. He started out in 1979, when a buddy purchased a small pest management firm and convinced Carter to buy one, too. A year later, Carter bought his buddy’s firm — and today services much of the southwestern U.S.

Bruce Carter is on Copesan’s bird control committee, which garnered him a “Bird Brain MVP” award along with his fellow committee members.

He offered bird service essentially from the beginning, but admits it has evolved. These days, Carter Services does approximately $250,000 a year in bird control work, the majority of it translating to netting jobs for the “Big 3” species: pigeons, sparrows and starlings. Overall, Carter Services is about 98 percent commercial; Carter says his bird work is 100 percent commercial to stay profitable.

How has he consistently achieved success? For starters, Carter is a stickler for working alongside his crew to get the jobs completed on time and on budget. Indeed, the first time we called to interview him, in mid-February, he couldn’t come to the phone because he and his team were working on a netting job at a warehouse in Colorado Springs, Colo.

When we finally got the chance to talk to Carter, we learned the weather had pushed the job from a one-day to a two-and-a-half day project. It snowed in Colorado Springs the night before the project began, and when the work started, it was 4°F. Work progressed, but trying to stay warm during installation meant frequent breaks. That’s why being flexible and considering wild card factors are so important when bidding, preparing and doing bird jobs, Carter says.

“I get into the mix with my guys because I can’t expect them to do something I wouldn’t do,” he adds. “Plus, I enjoy working.”

Chris McCloud: Market to your clients

Chris McCloud, president and CEO of South Elgin, Ill.-based McCloud Services, also has a pest control company that is almost exclusively commercial. Drilling down further, the majority of its revenue is from the food industry. McCloud also does a fair amount of work in other areas including health care, hospitality and property management.

“All of these companies are also very good bird control accounts,” points out McCloud, a fourth-generation owner of the 104-year-old firm. “As long as we have been doing pest control, we have been doing bird control work in one form or another. But in the past 50 to 60 years, bird control has become a key component of our integrated pest management (IPM) program. We are comfortable performing any level of bird control work, from large-scale netting jobs to smaller things like signs on retail stores.”

McCloud says the company has done some bird control jobs that had revenue in the range of $100,000 — government post office work, for example.

“Our customers are always looking for bird control solutions,” McCloud says. “As people continue to be more concerned with public health issues and the aesthetics of their work environment, bird control has become a big, growing segment of our business that is only going to increase.”

McCloud Services has offices in seven Midwestern states, and does business in a total of 10 states. It trains every technician in bird control with the help of a supplier-based program. But while every tech ends up with some bird service knowledge, an elite few comprise the backbone of the bird control team.

“We have a dozen or so people who are very skilled at bird control work, so when we have a large-scale job, we are able to source that group and perform the work,” he explains, adding that there is never any shame in asking for assistance or for more information. “If our technicians can’t solve a bird problem themselves, they know enough to ask a lot of questions.”

Frank Giannico: Learn more every day

For Frank Giannico, commercial services manager for Clark Pest Control in Santa Maria, Calif., bird control work is an interesting process that often requires both time and patience.

“I’m constantly learning on a daily basis,” says Giannico, who notes that his construction background has been an asset in bird work. “The best way to learn about bird control is after you have finished your install. Wait around for an hour or two, and see how the pest birds react to the exclusion you have put into place. You can learn a lot about how successful you are going to be.”

Clark Pest Control, founded in 1950 and based in Lodi, Calif., has 23 locations throughout California and northwestern Nevada. Commonly encountered pest birds for the team include pigeons, seagulls and grackles. Giannico, who has been involved in bird control for 13 years, remembers another common bird, the swallow, as being the reason for one of his most difficult jobs.

“There were swallows on the back wall of a hotel, with droppings all over the fourth-floor windows, which were ocean view rooms,” he says. “That job involved scaling up the back side of the hotel with a lift. The hotel needed to have that problem addressed immediately, and we were able to accommodate them.” The upside? “I had an ocean view from the lift,” he says, tongue-in-cheek.

Giannico concludes with one more tip gleaned from his bird control work when bidding on a job: “We say, ‘Send us a lot of pictures, dimensions and information on what we will be drilling into, and we will do our best to help.’”

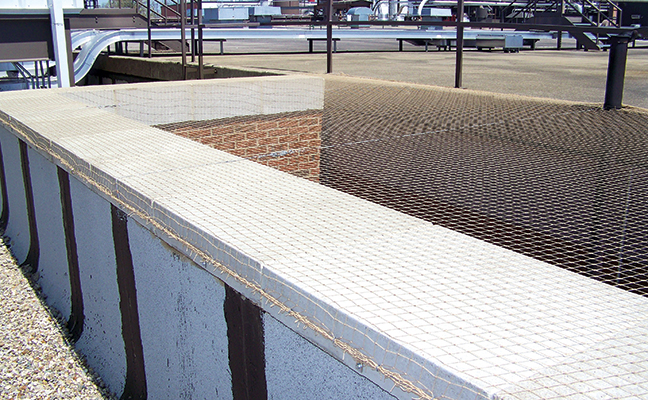

- Giannico advises checking back in an hour or two after initial install of something like this electrified track, to gauge the birds’ reaction. Photo: Clark Pest Control

- McCloud Services’ bird prevention measures help grow the business. Photo: Clark Pest Control

- McCloud Services’ bird prevention measures help grow the business. Photo: Clark Pest Control

- Clark Pest Control protects the stucco walls of this building with bird netting under the eaves. Photo: Clark Pest Control

David Kane: Prepare for challenges

In New York City, the thermometer said it was 70°F. That made residents believe spring was just around the corner on this late-February day, even though that is rarely the case.

David Kane, treasurer of Manhattan-based AKA Pest Control, also manages the division appropriately called “Bye, Bye Birdie.” He took advantage of an unusually warm day to check out the water towers of two local hospitals for a couple of bird control projects.

In the winter, pigeons tend to move into the water towers, he explains. And when it’s time to change the water towers’ air filters, workers won’t go into the towers until the towers are cleaned and disinfected.

“Both of those jobs are basically netting,” Kane says. “These hospitals are already customers, so we move them to the top of the list.”

AKA operates in the tri-state area of New York, New Jersey and Connecticut, primarily focusing on commercial accounts — hospitals, nursing homes, universities and office buildings in particular. When asked about some difficult bird control jobs the company tackles, though, Kane pointed to the railroads.

“These are some of the most challenging jobs we do because of the permits required for road closures to gain access to the undersides of railroad bridges,” he explains. “The hardest part is when you protect one area, and the birds then just move to another area, on the left or on the right. It’s one continuous job.”

In addition to the public image issue for railroads, there’s also potential damage done to wiring and steel from bird droppings and urine, Kane says. When workers need to be in enclosed areas, the chance for disease increases, too, he adds. It’s why his team must be thorough during inspections, treatment and follow-up, he says.

“We go back and re-inspect an area to make sure everything is up and running correctly,” he adds, noting that AKA conducts quarterly inspections. “Sometimes we have to clean the area and do a reinstall.”

Contrubutor Jerry Mix, a 2005 PMP Hall of Famer, can be reached at pmpeditor@northcoastmedia.net.

Leave A Comment