Blackbirds are a protected species under the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act, but that doesn’t make them any less of a nuisance. It simply means the red-winged blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus) and just about every other bird species — with the exceptions of sparrows, pigeons and starlings — can only be controlled under very specific circumstances.

In our September 1978 cover story, “Nonlethal Blackbird Roost Control,” Drs. Heidi Good and Dan Johnson detailed a way to deter blackbird roosting that is simple in its elegance: tree trimming.

Drs. Good and Johnson field-tested their approach at the 300-acre Rice University in Houston, Texas, which they estimated supported a blackbird roost of about 500,000 every winter. Dr. Good received her doctorate in 1979 from Rice; this was her thesis project. Today, she is primarily involved in genealogy, volunteerism and research of all stripes. At the time of publication, Dr. Johnson was a zoologist with the department of biology for East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, Tenn. By 2000, Dr. Johnson was chair of the university’s department of biological sciences. He has since retired.

What follows are excerpts from their report:

The birds involved are 80 percent male brown-headed cowbirds, with female cowbirds and both sexes of redwings, common and great tailed grackles, starlings and robins making up the rest.

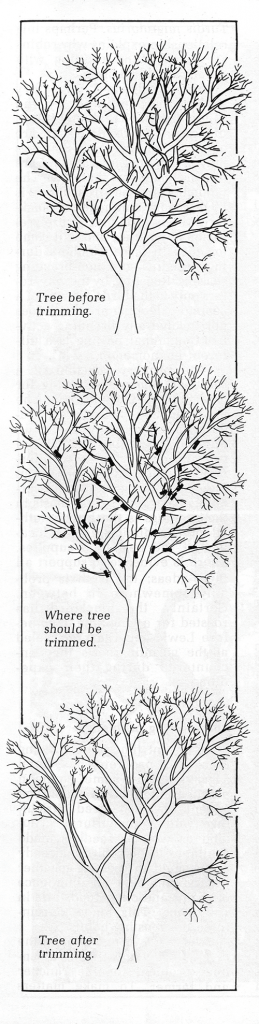

The roosting habitat is live oak trees (Quercus virginiana). These trees were planted in groves between buildings and in large open areas in 1912, and now form a closed continuous canopy. The trees had not received regular maintenance for five years before the roost began to form on campus in the early 1970s. As a result, the trees were very bushy and formed a dense matrix of twigs and leaves, extending over an acre in some places. Tree trimming seemed an obvious habitat modification procedure.

We did not attempt to trim all 4,000 trees on campus. Instead, we used an experimental approach and trimmed only a few groves each year, several months before the birds’ anticipated arrival. This left the majority of the roosting trees undisturbed. [Editor’s Note: The authors say this was a control measure, although other factors could come into play.]

In the presence of an active roost, we were able to prevent roosting in particular groves for up to three years by trimming out one-third of the canopy of all the trees in the grove… It was possible to eliminate birds from an entire grove by only trimming the most actively used trees… We found that the favorite trees were the same from night to night and year to year, and were also the first to be occupied each fall…

Extrapolating from our results with live oaks, the following recommendations can be made.

- It is best to trim or remove trees before the birds’ anticipated arrival; it prevents the roost from ever being initiated. The longer the birds have been roosting, the more difficult they become to displace. However, it is possible to remove a roost by trimming after the birds have become established.

- Until the birds find another suitable roost to use annually, it will be necessary to keep the trees trimmed to retain control. This becomes especially important if only a part of the roost can be managed. If, for example, a homeowner has part of a roost on his property and the owners of the rest of the roost are not prepared to cooperate, yearly pruning of the affected trees on his property should keep them from his property.

You can reach Editor Heather Gooch at hgooch@northcoastmedia.net or 330-321-9754.

Leave A Comment