Drywood termite feces have a unique feel that can be identified with an educated touch. PHOTO: MATT REMMEN

Pest management is all about making good decisions. Those decisions are often based on what is observed, and those observations are guided on what we see. However, all five senses we have are crucial for making the best decisions. Using these senses with keen deductive reasoning and shared experience to identify where or what is happening with cryptic pests is crucial to our success. When training your team, or preparing for a site inspection yourself, consider how to train each of the senses to identify a problem.

SMELL

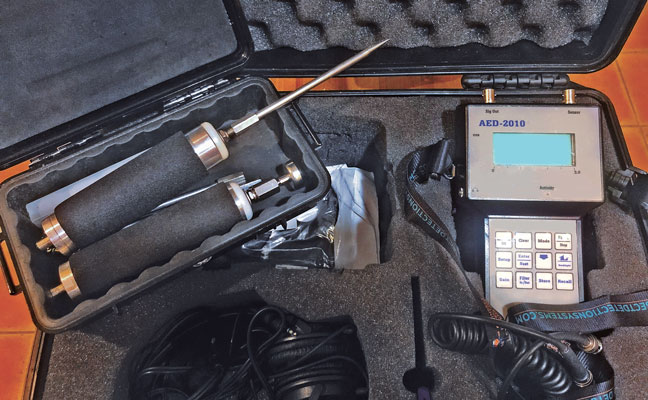

Specialty tools such as this IDS 2020 can provide indirect observation and confirmation of cessation of activity. PHOTO: MATT REMMEN

Our sense of smell is often underrated, yet critical when solving cryptic pest problems. Smell can lead us to a bathroom with a degraded wax seal, letting in American cockroaches (Periplaneta americana) from sewers or septic systems. It can also let us know that a rodent has chewed through a vent stack — or even that the vent is clogged, and a plumber needs to be called. Some smells are more important for residential or commercial technicians, but here are some we should train ourselves and our pest management colleagues to recognize:

- Sewage: For overflows, degradation of pipes/wax rings are a key indication of cockroaches, house flies, phorid flies, soldier flies and other issues. If you don’t have a water treatment facility nearby, ask your technicians to recall what their homes smelled like when they had a plumbing backup.

- Rodent urine and fecal pellets: Visit the local pet store yourself or with your technicians to help identify rodent issues and quickly ascertain the presence of the cryptic pests. While house mice and rats can have slightly different odors from person to person, either smell necessitates further exploration.

- Fried food/Fast food: Demonstrate the distance at which we can smell the odors, and relate to how much farther a house fly can smell and track down the food presence. This is a fantastic way in which the technician can emphasize the closed doors, proper screening and functioning door sweeps as a key part of pest management.

- Yeast, rotten fruit and stale beer: For fruit flies, the smell of fermented sugary foods is a major component to locating breeding sites. If access to a dive bar isn’t an option, then a bakery is a good analog. Use that smell to help locate sources of debris that flies will inevitably find before you.

- Bed bugs: For major infestations, the odor is often described as berry-like, but it also can present as a musty odor. Unfortunately, there isn’t a good way to experience this odor unless you have an account with a severe bed bug infestation — or have a collection of, or access to, bed bugs.

- Ants/Acetic acid: Open a bag of salt-and-vinegar potato chips, inhale, and you’ll get a sensation of what a disturbed colony of carpenter ants smells like when working in a customer’s attic. Vinegar doesn’t seem too upsetting, unless you aren’t ready for a noseful of it.

- Ants/Rotten coconut: Perform the squish test of odorous house ants (Tapinoma sessile, or OHA), which have a distinct smell. Note: If you don’t know how to pick up an ant, lick your fingers and lightly press on the ant. Many folks describe the smell of a squished OHA as analogous to rotten coconut.

- Ants/Citronella: Lasius interjectus and L. claviger — larger citronella ant and smaller citronella ant, respectively — certainly smell like their common names when squished. You can probably find a citronella extract or similar in a flying-insect repellent at your local outdoor store.

There are plenty of other bugs that really don’t require using our sense of smell to identify, as they aren’t as cryptic, small or hard to identify as others, but they can smell anyway. For example, if new technicians want to learn what brown marmorated stink bugs (Halyomorpha halys) smell like, suggest they do it somewhere else.

SOUND

Termite damage can be hidden. Above, the front side of this painted 2×4 looks fine; it’s this back side that reveals the damage. PHOTO: MATT REMMEN

Sound is a very useful and often underappreciated tool for pest management. Some make pests of themselves just because they make noise, while others may be noisy as they damage the homes and buildings in which we live and work. Cicadas and crickets are commonly thought of when we discuss noise; however, drywood termites, carpenter ants, rats, mice and others can sometimes be heard and give us the information needed to determine their presence. Because much of what we do is deductive, and we can’t destroy the things we need to inspect, we can use several tools for identifying pests.

A handheld acoustic emission instrument such as the IDS-2020L, online at Insectdetectionsystems.com/products/acoustic-instruments, is tuned to the sound wood makes as it is broken off and consumed by drywood termites. This sound is often described as “popcorn popping,” but an analog TV on a gray screen is analogous as well.

Old house borers are described as producing a short rasping sound. Rats, mice, bats and other vertebrates can also be heard entering, exiting or foraging in homes.

Cessation of noise is useful, too, in determining whether control of these pests was achieved. This concept of indirect observation, including the cessation of noise, is a key component to demonstrate control to a new technician.

However, be forewarned that sound doesn’t always help you. Sound can also impart stress, such as the scream of a leg-caught rat.

TOUCH

Touch is one of the least-used tools, as the presence of pests doesn’t inspire confidence in sticking hands and fingers into dark holes, even if we know the worst that will happen is a cockroach hopping a ride out on our digits. Touch, especially when combined with sound, is a masterful way to detect voids, damaged wood, rot, and even moisture.

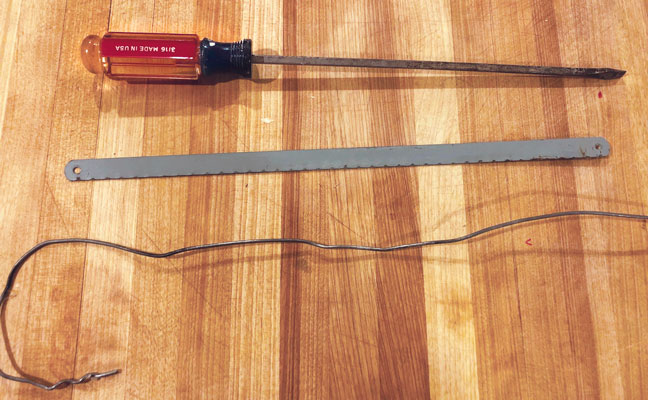

There is an experience in either driving out or feeling the crunch of a cockroach inside a void. You can also use a long-bladed screwdriver as a sounding tool and probe for hard-to-reach areas when dealing with wood-destroying pests.

Touch with bare fingers is a great way to demonstrate to a technician a simple technique to identify a pavement ant. Unlike the OHA, which easily squishes apart, Tetramorium caespitum feels gritty when squished.

If you want to really learn more about touch, you can delve into the differences between drywood termite frass and wood-destroying beetle frass. The former is large and feels like a small, crushable pebble, while the finest frass from certain wood-destroying beetles feels like talcum powder.

SIGHT

Tools can even be homemade, a la this wire coat hanger, to suit the situation. Long, thin, flexible tools for probing and long, hard ones for sounding are ideal. PHOTO: MATT REMMEN

Sight, while the last of the direct senses discussed, is notably the most important. We can’t process all the stimuli our optical nerves perceive, so our brain consciously ignores much of what we “see.” As an example, do you remember every part of every drive to your customers’ locations in the past month? While we can only focus on limited stimuli, training cognizance of certain visual cues will lead to success. Attuning yourself to shade patterns and identifying animal runways, and general impressions and sizes/shapes will help train technicians on where to look for wasp nests and rodent burrows, and identify ants from many feet away. Using knowledge such as how yellowjackets or bald-faced hornets fly to their nests will allow technicians to move into position so they may identify where pests are entering without alarming them. Doing this without getting stung is an art form, and necessary for the safety of both techs and homeowners.

Sight also can be useful in observing situations such as detritus below a bat entry point, carpenter bee damage, rodent rub marks, and debris/dead compatriots from carpenter ants. Using light as a silhouetting tool helps identify fruit fly larvae in a drain. There are many more examples of clues and tips, and you are best served by polling your field staff for those local insights.

Newer technology can complement and enhance our senses. We can augment our abilities with tools such as thermal cameras, moisture meters and remote monitoring devices. These tools can identify heat discrepancies and are useful in locating beehives — as well as roof leaks and other non-pest issues. Remote devices such as rodent traps and game cameras can help detect what happened and document when it happened, so we may use that information to solve the issue.

THE SIXTH SENSE: COMMUNITY

Staying on top of the latest technologies (and personal protective equipment) sets you apart from the competition. PHOTO: MATT REMMEN

Last, and most important, is our sense of community. Sharing experiences among seasoned and new staff members with diverse backgrounds, such as building construction, agriculture, maintenance and more, is key for exposing problems and how to resolve them. Local offices often have unique building techniques or codes that lend themselves to pest issues.

Specific pests, such as Formosan subterranean termites (Coptotermes formosanus), can arrive in communities at regularly scheduled times during the year that may only affect a particular office. For some communities, they can seasonally experience an explosion of rodents, grasshoppers, beetles or specific agricultural pests that may stump technicians in different locations.

Use your sense of smell, hearing, touch, sight, and sensory enhancers of technology and experience to fully realize your abilities. Training a new technician to use the senses is very important, and the art of detection in pest management can be highly nuanced.

(My apologies if your favorite restaurant is ruined now that you’ve realized the smell when you walk in may not be the love they put into the recipe.)

Leave A Comment