Photo: Avector/iStock / Getty Images Plus

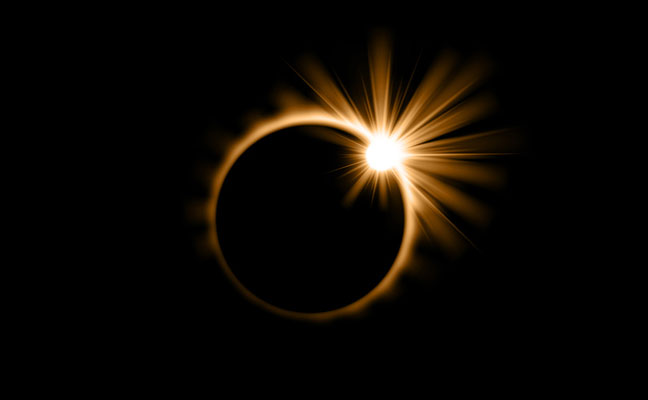

The next total solar eclipse will pass North America on April 8, which will have the day turn to darkness and potentially effect the behavior of pests.

According to an article from The Washington Post, “Reports abound of unusual animal and plant behavior during eclipses. A swarm of ants carrying food froze until the sun reemerged during an 1851 eclipse in Sweden. A pantry in Massachusetts was ‘greatly infested‘ with cockroaches just after totality in 1932. Sap flowed more slowly in a 75-year-old beech tree in Belgium in 1999. Orb-weaving spiders started tearing down their webs and North American side-blotched lizards closed their eyes during an eclipse in Mexico in 1991.”

Team across the country produced a swarm of studies about plant and animal behavior during the last total eclipse to cut across the U.S. in 2017.

Some of these scientists found that when the sun vanished, insects, birds and plants seemed to enter into something approaching a nocturnal pattern. For example, scientists in multiple states reported that fireflies started flashing, and a team in Idaho captured two species of voles that are normally active at night. However, bat researchers in Georgia weren’t convinced that the eclipse had any effect on behavior, though they noticed slightly more bat activity on the night after the eclipse than on previous or subsequent nights.

When Pest Management Professional reached out to the National Pest Management Association’s (NPMA’s) technical team, they said they predicted there would be little impact on pests or pest behavior.

Birds

One common report is that birds go to roost and go quiet during an eclipse. A team of ornithologists from Cornell University made recordings along an old logging road near the town of Corinna, Maine, for the 1963 eclipse, they heard the per-chic-o-ree of a goldfinch in the middle of totality, along with a hermit thrush, a Swainson’s thrush and a veery.

“Perhaps no two lists of birds heard before, during, and after the eclipse would be anywhere near similar,” they wrote in the summary of the observations.

In the 50 minutes before and after totality in 2017, researchers monitoring flying insects and birds via the weather radar network found that the skies went eerily quiet, but there was an intriguing uptick of activity right at totality. The researchers speculated that it might be some kind of insect reacting to the sudden darkness, while the birds possibly grew still due to confusion.

“Some previous research shows that insects react much more immediately to light cues, while birds are more like, ‘What’s going on?’” Cecilia Nilsson, a biologist at Lund University in Sweden, told The Washington Post. “Totality only lasts a few minutes, so by the time you’re figuring it out, it’s over.”

One aspect of the 2024 eclipse is that it is happening during the spring, whereas the North American eclipse of 2017 took place very early in the fall migration season, Nilsson said. Many birds, she noted, migrate at night and are often more motivated during the spring migration, so it’s possible that abrupt darkness will have a different effect this time around.

Honey bees

Olav Rueppell, a scientist who studies honey bee biology at the University of Alberta in Canada,was based in North Carolina during the total eclipse in 2017. He decided with collaborators to try to bring some rigor to previous observations of honey bee behavior.

A crowdsourced compilation of observations from a 1932 total eclipse, for example, included reports of a swarm of 200 bees showing “apprehensiveness” in the minutes before totality. Another observer reported that “as darkness increased the outgoing bees diminished in numbers and the return battalions grew larger.”

Rueppell and colleagues at Clemson University in South Carolina enlisted observers to watch the entrances of hives, counting how many honey bees were exiting and how many were returning from foraging trips before, during and after totality. They made some hives hungrier than others by taking the bees’ honey away before the eclipse, to see if that changed their willingness to forage.

The researchers found that the environmental cues overrode bees’ own internal circadian clocks, with darkness causing them to return to the hive and hunker down. Those findings square with another study that found bees stopped buzzing around flowers during totality. But hives that were stressed by hunger shut down less completely than those that weren’t.

They also conducted a second experiment, putting fluorescent powder on bees and releasing them away from their hives, then measuring how quickly they returned.

Right before totality, they found the bees were returning faster, almost as if they were panicked.

Check out the full article from The Washington Post that shares what other studies plan on being conducted with zoo animals and forests for the upcoming eclipse.

Are you planning to watch the eclipse on April 8? Let us know in the comments and share us your solar eclipse photos at pmpeditor

Leave A Comment