Once upon a time, when you bought a book containing scientific facts, those facts stayed the same. No matter how long between uses, when you pulled that book off the shelf, there were still nine planets in our solar system, dinosaurs had scales instead of feathers and termites had their own order (Isoptera).

Okay, maybe I’m exaggerating just a little, but you get my point. For those of us who struggle to memorize stuff, getting it down right just once is challenging enough. Nowadays, though, it seems like the experts are changing things up non-stop.

What’s going on?

As pest management professionals (PMPs), most of us have a little scientist inside our heads who tries to understand how things work and how everything ties together. Am I right? Well, lately, my little scientist has come to the conclusion that a great number of scientific “facts” aren’t really facts at all; they’re more like trending best guesses (okay, scientific hypotheses) that are subject to change at any time.

I suppose I should be glad that humanity is constantly fine-tuning our knowledge of the universe, but it’s all the pit stops between the starting point and the goal of “Yep, we’ve arrived,” that get to me. I feel like the kid in the back seat of the family minivan who keeps yelling out, “Are we there yet?” Probably the most pronounced example of this is how the standards of taxonomy are expanding and contracting, with no end in sight.

First, a little context

The traditional way of sorting out critters was the brainstorm of Carolus Linnaeus, an 18th-century Swedish naturalist. He formalized our system of naming organisms using binomial nomenclature. Every known living thing has been assigned genus and species names. It was all translated into Latin and Latinized Greek, because in those days, Latin was the universal language of scholars.

Well, that was a good start — but then came Charles Darwin in the 1800s. He began to propose a hypothesis of ancestry and origins for extant organisms based on their anatomical (morphological) and biological/behavioral similarities and differences, as well as their geographical distribution. Darwin and his protégées organized organisms into levels of relatedness based on perceived evolutionary changes over time. The result was something called the phylogenetic tree, or “tree of life.”

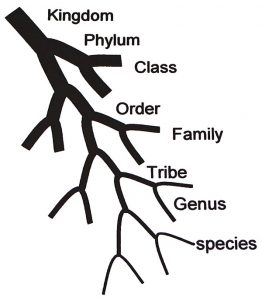

If living organisms could be compared to leaves on the tree of life, the traditional placement of those leaves would be arrived at by tracing the main branches from the trunk, outward along finer and finer branches, until we reached the twigs. Likewise, the traditional taxonomy of living things follows a path from the general to the specific as follows:

Kingdom

–Phylum

—Class

—-Order

—–Family

——Tribe

——-Genus

——–Species

There can be even more fine-tuning of these taxonomic levels, resulting in intermediate levels, to allow for the promotion, demotion or insertion of taxonomic levels to accommodate changes:

Order

–Suborder

—Infraorder

—-Superfamily

——Epifamily

——-Family

——–Subfamily

… and, well, you get the idea.

Tweaking the tree

Ever since the days of Darwin, scientists who specialize in systematics and taxonomy have taken it upon themselves to carry this tradition forward, “tweaking the tree” as they go. More recently, though, it seems more like these scientists have been giving that tree of life a good shaking. The reason? Recent advances in computer analysis and cybergenetics.

Geneticists have buddied up with computer geeks to piece together the entire genetic complements, or genomes, of a growing list of organisms. Genomes range greatly in size, but all are amazingly complex. The Escherichia coli bacteria in your intestine, for example, have 4.6 million bases (“rungs” of the DNA “ladder”) comprising 3,000 genes (instruction-encoding segments of DNA). The genome of the familiar red-eyed fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, contains 165 million bases. We humans have 3.2 billion bases in our genome.

The current trend of molecular-based classification hinges on a comparison of the nucleotide sequences of the 16S rRNA (encoding) gene of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) extracted from the specimens in question. (Author’s Note: You can look all this stuff up online on Google and Wikipedia like I did. I certainly haven’t committed all this jargon to memory. By the way, mitochondria are organelles important for cell metabolism and energy production.) Whether the key sequences chosen for evolutionary relatedness are sufficiently reliable to make these determinations, however, is open to question.

What this means for PMPs

Truthfully, in your day-to-day business, the latest taxonomic upheavals probably won’t affect the success of your methodology and efficacy. The changes could, however, affect your score when you test for a new applicator category certification or license if your state regulatory agency keeps current with the aforementioned trends and modifies the applicator category exam questions accordingly. The changes definitely will affect your score if you test to become an Associate Certified Entomologist (ACE) to enhance your credentialing and curriculum vitae (CV).

Staying current with pest arthropod taxonomy also will make a difference if you are the one responsible for training new employees for your company, or if you are invited by a state or local pest management association to speak or write an article on a particular group in which changes have occurred. No one wants to be confronted by peers during a presentation and be embarrassed for lack of current information.

The reality is, your favorite online search engine can be your friend — as long as you use multiple sources, not taking just one reference’s word for it, of course. When typing in the specimen name you know, try also typing in the terms “taxonomy,” “BugGuide” and “tree of life.” If there has been a change, you’ll have some choices pop up that will point you in the right direction. Happy hunting!

Dr. Gerry Wegner, BCE, is retired technical director and staff entomologist of Varment Guard Environmental Services, Columbus, Ohio, and currently resides in Florida. Contact him at pmpeditor@northcoastmedia.net.

Leave A Comment