Extensive media coverage can lead to concerned customers. Education (and some precautions) can mitigate the scariness of it all.

As of now, the avian, or bird, influenza epidemic of 2016-17 hasn’t reached North American shores on a large scale. But various strains of the virus are devastating parts of Asia, Europe, the Middle East and North Africa, and the World Health Organization (WHO) reports the transmission risk factor is serious. Nearly 40 countries have reported new outbreaks in poultry and wild birds. In some instances, it’s led to large-scale slaughters of poultry — and in China, several human deaths also have occurred.

This year’s viruses include H5N6, created by gene-swapping among four different viruses, and H7N7, which has shown a sudden and steep increase of human cases since December, according to a report by Dr. Margaret Chan, director-general of WHO. While most countries are better equipped to fight the pandemic than they were during the H1N1 virus outbreak of 2009-10, the causes and spread of the viruses still are not fully understood. In fact, a new avian flu is the No. 1 fear of biological security experts, who know flu causes regular pandemics among people, sometimes killing millions in months, according to NBC.

In December, the H7N2 strain of the virus infected 45 cats in a Manhattan animal shelter. Humans and dogs at the shelter weren’t affected by the respiratory virus, and only one cat, which was elderly, died. The outbreak was mild, experts say, and while the originating source remains unknown (the strain is associated with chickens), it seems it was contained to the shelter.

In January, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) confirmed that a wild mallard duck in Montana died from H5N2. This particular strain of bird flu affected farms in 15 states in 2015, leading to an estimated $3.3 billion loss because of the culling of more than 42 million poultry. At press time, researchers are testing thousands of waterfowl to ensure other cases aren’t populating. So far, the case seems to be isolated.

“This is a mystery we don’t have answers to, but it’s telling us the avian influenza virus is capable of adapting to all sorts of situations,” said Dr. David Morens, a senior advisor at the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, in a January interview with the University of Minnesota’s Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP).

Dr. Morens also noted that the 2015 epidemic was more likely because of human actions, rather than waterfowl spreading the virus to chickens. Mindful of that, the USDA has recommended the “Danish Entry” system, in which each person entering a farm sits at a bench in an entryway to change shoes and clothes. The process provides a physical barrier to outside pathogens.

“Agricultural workers need to recognize the clinical signs faster, but everyone has a role in halting avian flu, whether it’s the UPS driver who stops by the farm or the worker taking care of the birds on a daily basis,” Steve Olson, executive director of the Minnesota Turkey Growers Association, told CIDRAP.

The PMP’s role

Pest management professionals (PMPs) have known to take precautions when dealing with birds for various potential diseases, including histoplasmosis, salmonella, fungal meningitis, toxoplasmosis and paratyphoid. Wearing masks, long sleeves and gloves when cleaning up droppings and disposing of carcasses, for example, help protect against such diseases.

“While human cases of avian flu are extremely rare, they have occurred,” reminds Dr. Jim Fredericks, chief entomologist for the National Pest Management Association (NPMA) and a PMP columnist. “Aquatic birds, including gulls and waterfowl like ducks, geese and swans, are considered potential reservoirs, as are chickens. If it’s necessary to handle sick or dead birds, gloves should be worn. When removing bird droppings of any species, PMPs should practice proper precautions such as disinfecting surfaces and wearing gloves and respiratory protection to avoid infection with avian flu or other diseases, such as histoplasmosis or cryptococcosis.”

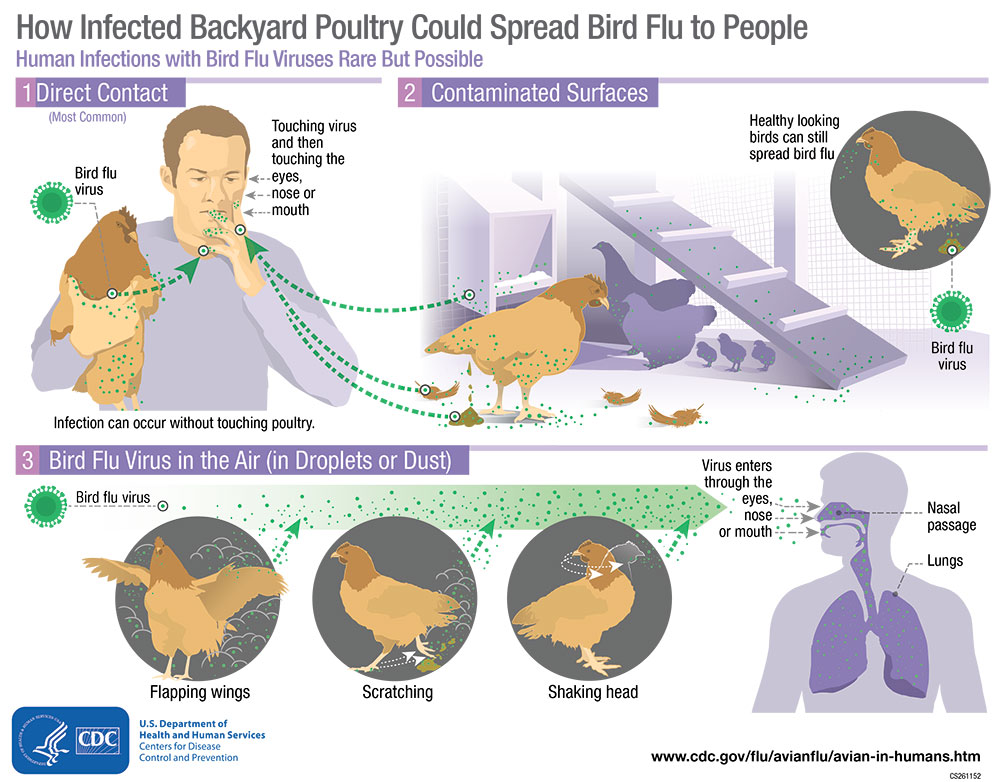

For some customers who are learning about bird flu online, on TV or in the newspaper, it can be frightening. Compound this with the trend for suburban homeowners to keep a couple chickens in a pen for egg production or feed wild ducks attracted to a backyard water feature, and it’s worth familiarizing yourself and your team about its prevention — and reassuring them of the minimal risk.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) recommends avoiding sources of exposure whenever possible.

“We don’t receive many questions about it, but when we do, we simply tell them it’s mainly related to poultry overseas, and that bird-to-human contamination has been extremely rare thus far,” notes Rodney Beaman, president of Texas Bird Services and Fort Worth Pest & Termite Services. “Then we direct them to the CDC’s website for more info. We also use precautions and recommend precautions working around any feces from any bird.”

Recommendations from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention

- Avoid wild birds, and observe them only from a distance. Avoid contact with domestic birds (poultry) that appear ill or have died.

- Avoid contact with surfaces that appear to be contaminated with feces from wild or domestic birds.

- People who have had contact with infected bird(s) should monitor their own health for possible symptoms — conjunctivitis (“pink eye”) or flu-like symptoms, for example.

- People who have had contact with infected birds might also be given influenza antiviral drugs preventively.

- Healthcare providers evaluating patients with possible HPAI H5 infection should notify their local or state health departments, which, in turn, should notify CDC. CDC is providing case-by-case guidance at this time.

- There’s no evidence any human cases of avian influenza have ever been acquired by eating properly cooked poultry products.

- CDC will update the public as new information becomes available.

[Related: Was the 1918 flu pandemic caused by birds?]

Good article! Pithy, short, useful information that PMPs should consider for future service offerings. Bird control is an important and valuable service that truly serves the public by providing important public health benefits.