An odorous house ant that has yet to darken “clearly” stands out among other workers as they feed on gel. PHOTO: DR. KAREN VAIL

Author’s Note: This article was adapted from “Environmental modifications around a Tennessee home unintentionally reduce odorous house ant populations” in the Proceedings of the National Conference on Urban Entomology, and used with permission. See the original article online at Entomology.TAMU.edu.

Are you taking the time to identify an ant species before you begin treatment? Confuse an odorous house ant (Tapinoma sessile, or OHA) with an Argentine ant (Linepithema humile), and your management protocol won’t change much. Apply a soybean oil-based fire ant bait for OHA, though? You’ll be wasting your time and money because OHA rarely feed on plant oils. And doublecheck that label — the species probably is not listed for that very reason.

Going forward, specifically with OHA, a common household pest that is often easy to mistake for other ant species:

- Do you inspect the entire premises for signs of OHA?

- Do you place honey on index cards every 10 to 20 feet around the perimeter of the home to detect areas of high OHA activity?

- Do you bait these areas of high activity, and treat nests as they are found — and/or apply a slow-acting product to the perimeter and potential entry points?

- Do you correct conducive conditions, suggesting clients remove the food, water and potential nest sites of this ant — better yet, correcting the conditions for clients?

CASE IN POINT

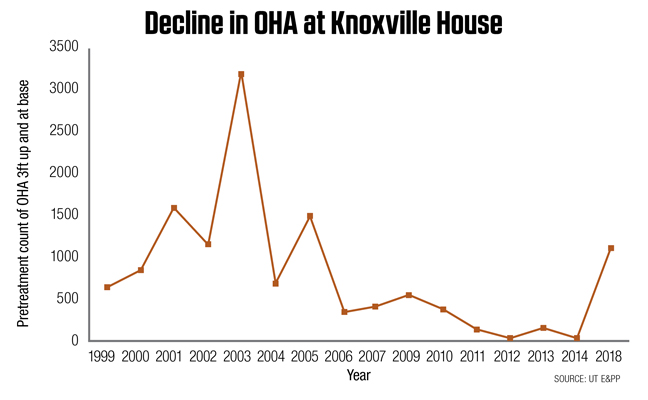

Decline in odorous house ants (OHA) following environmental modifications around the author’s house. SOURCE: UT E&PP

My home is in a Knoxville residential subdivision and is one of the few structures included in various University of Tennessee (UT) OHA-focused research studies that never receives pest control treatment. For the past two decades or so, it’s referred to as a control structure because it’s used to help researchers understand the effects of natural changes in the environment, such as excessive rainfall or lack thereof, extremely high or low temperatures — anything that changes the number of OHA found around a home.

In Tennessee, the number of OHA around a house typically increases from May through August. If the number declines, we want to ensure it’s due to the effect of a treatment under study, and not natural changes in the environment.

In the beginning, in the late 1990s, OHA were abundant and many nest sites were readily found on my property. You could look at most places that retained moisture and provided shade, and within minutes find an OHA grouping. Nest sites included mulched areas; leaf piles; in soil along iris rhizomes; under scrap siding, roofing or stucco laying on the ground; in between logs of stacked firewood; under and within the landscape timbers surrounding the concrete patio; and under the top board of a honeybee hive.

Odorous house ants (OHA) in a leaf pile.

OHA nested under a 50-gallon exterior trash can during the warmer times of the year, then moved to a gap around the indoor garage door frame to overwinter. This was a very efficient use of their energy: The area under the garbage can provided the OHA protection from predators, yet gave them moisture from condensation and a food source just a few feet away. Similarly, the garage door was only a few feet from the garbage can.

OHA formed visible foraging trails. They often used the home’s structural guidelines, such as the base of the house; the edge or cracks in sidewalks, porch and patio; and the rough texture of stucco. The ants foraged to various food sources, which included:

- An outdoor dog food bowl.

- Dead insects on the porch and patio.

- Dead animals (skunks, rodents, snakes, birds, rabbits, etc.) that our cat left as gifts.

- Nectar from rhododendrons.

- What we assumed to be honeydew from sucking insects on azalea, silver maples and pine.

- The kitchen and bathroom garbage cans.

Crumbs left in the dog bowl provided food for the odorous house ants (OHA). PHOTO: DR. KAREN VAIL

PRETREATMENT STRATEGY

Before including a house in any OHA management study, pretreatment counts are taken by placing a honey-smeared card every 10 to 20 feet around the house: at

3 feet above the base; at the base of the foundation wall on the ground; and 7 to 8 feet on the ground, away from the house in the landscape.

Cards are left in place for 40 minutes, then the ants are counted and tapped off the card. Pretreatment counts presented in the chart on p. 40 are a sum of the ants on the cards at 3 feet up and at the base, from 2000 through 2014, and 2018. Pretreatment OHA counts trended upward through 2003, peaking at 3,209.

Odorous house ants (OHA) followed lines of textured stucco that was in the shade of the rhododendron. Ants entered under the hardboard siding, and followed guidelines to emerge at the pipe penetration by the kitchen garbage can. PHOTO: UT E&PP

You will notice an obvious decline in OHA numbers after 2003, so let me explain what happened: In 2004, the first in a series of environmental modifications occurred, and pretreatment count numbers began to decline. An ecological ant study was being performed around my home and other Knoxville houses, and participants were asked to refrain from modifying their landscape for the duration of the study. And we tried — but sometimes things happen over which we have no control, specifically:

- 2003 was the first year in which cypress mulch was not applied to the front yard landscaping.

- Between 2004 and 2010, several trees and shrubs were removed.

- The rhododendron on the back of the house died, was removed, and thus no longer shaded the ant trail into the house nor provided a nectar source.

- The pine and azalea in the mailbox bed were removed, as were the two silver maples. Ants had been foraging into all of these.

- OHA were nesting in landscape timbers surrounding the patio. But the timbers were rotting and replaced with formed block. Ants were never seen nesting under the block.

- A shade plant garden was created off this patio, and stretched down to an oak about 50 feet away. Mulch was added periodically, and pine needles and dried leaves also provided nesting sites away from the structure.

- My husband’s honey bees died out, thus removing a food source and nest site for the ants.

- The 14-year-old cat died in 2010, and the constant supply of carrion was lost. As a tongue-in-cheek aside, a certain PMP Hall of Famer (Class of 2015) and now-retired professor from the University of Florida, whose name rhymes with Phil Koehler and who is infamous for his aversion to felines, interpreted this data to indicate that cats were responsible for the OHA infestation, and if all residents removed their cats, they wouldn’t have OHA problems. Others may disagree.

- The aging dog refused to eat outside. It was too hot in the summer and too cold in the winter. Thus, another food source was lost to the ants. The dog bowl was moved to the interior side of the wall in the same location, but the ants never discovered it.

- The garbage can, which served as a nesting site and food source, was moved away from the garage door nest site (and spigot water source) to the less-conducive south side of the house, where it was surrounded by stucco walls, concrete pads and asphalt.

A SEA CHANGE IN OHA LEVELS

Odorous house ants (OHA) nested under the garbage can, which provided moisture from condensation, shade from the sun, protection from predators and close proximity to food. In the winter, the nest moved indoors, into a gap between the door frame and the block wall. PHOTO: UT E&PP

For 2013 and 2014, pretreatment populations at my house were at insufficient levels to be included in research studies as a control site. Once the decline in ant populations was seen as permanent, and not just yearly fluctuations, we started adding mulch to the front flower beds again.

In the winter of 2013, a new dog joined the family. He readily ate outdoors, so the old dog followed suit, but the younger dog enthusiastically removed any food crumbs from both food bowls.

We also filled liquid ant bait stations with sugar water. You read that correctly; we did not include any toxicant in the liquid bait stations, we just gave the ants their favorite food. But initially, little increase to the ant populations was observed.

Mulch has now been added periodically, and another young dog has replaced the older dog.

While no perimeter treatment studies were conducted in 2015, 2016 or 2017, pretreatment OHA counts were at 1,101 in 2018. Thanks to mulch and messy pets, the populations have rebounded and my house can, once again, be included in the UT Urban IPM Lab’s ant management strategies field evaluations.

I haven’t even publicly discussed the indoor OHA invasions that have occurred over the years. I wonder if this article will again cause my husband to ponder going on a late-night talk show to discuss how entomologists torture their families?

CORRECTING CONDUCIVE CONDITIONS

Integrated pest management (IPM) often is mentioned when discussing ant control, but how many professionals emphasize correcting conducive conditions, or offer such corrections as part of their management plans? Inevitably, if conducive conditions were corrected all at once, rather than over eight years, a permanent reduction in ant numbers could occur more rapidly — aided, of course, by the use of well-chosen products as needed.

DR. VAIL is Professor, Urban IPM Lab, University of Tennessee Entomology and Plant Pathology. Contact her at kvail@utk.edu.

Leave A Comment