Photo: Cwieders/iStock / Getty Images Plus/ Getty Images

A new study found that shorter and cooler season may prevent invasive spotted lanternflies (SLF), Lycorma delicatula, from developing into adulthood, preventing them from moving to northern and upland areas.

In a study published in September in Environmental Entomology, a two-year project conducted by a team of Pennsylvania State University scientists provides strong evidence to support predictions that the SLF’s potential spread will be limited by increasing altitude and latitude, saving places like the Appalachians of North Carolina and Green Mountains of Vermont from its colonization. Even in those places, however, a span of not much more than a proverbial stone’s throw or two away can make a big difference in the insect’s survival prospects.

The primary focus of the paper “was to study the seasonal development of SLF populations and develop mathematical equations based on seasonal degree-day accumulations to estimate the timing of key life-stage activity periods,” according to lead author Dr. Dennis Calvin, who recently retired from the College of Agricultural Sciences at Penn State.

According to a writeup by the Entomological Society of America’s Entomology Today publication, a degree day for entomologists is a measure of the time and extent to which temperatures are within the range that allows an insect to develop. For an insect to develop fully, it needs a particular number of degree days during which the temperature sits at a level that enables its development through each life stage. It is the so-called “Goldilocks Principle” at work — not too hot, not too cold, but just right. If the average temperature on one day is, for example, 10 degrees above an insect’s base threshold temperature for development, then 10 degree days are accumulated that day. The base threshold of development is the temperature at which insect development is essentially zero. Entomologists use accumulated degree days (ADD) to calculate the total heat demands an insect needs to develop through a stage or its entire life cycle. With ADD, scientists can peek into the hidden facets of insect growth and thus figure out the total heat demands required for survival.

The processes described in the new study should produce accurate predictions of the suitable geographic range of the SLF by evaluating its potential to complete a life cycle from spring egg hatch to fall egg deposition based on season length, expressed as ADD, at a given location.

Equations that predict the timing of SLF life stages could be a critical tool for pest management practices, such as monitoring and activating controls. Using the equations, the Penn State researchers were able to estimate areas lacking enough accumulated degree days for SLF to reach the adult stage, lay eggs and gain a foothold.

“If the timing of key life stages, as seen in field data, is consistent enough across years and/or locations to make sound management decisions, then pest managers can effectively time monitoring, surveillance, scouting, and control tactics,” the researchers wrote.

Calculations by the research team suggest that areas with fewer than 991 ADD are unlikely to provide enough time for females to emerge, mate, and develop mature eggs for deposition.

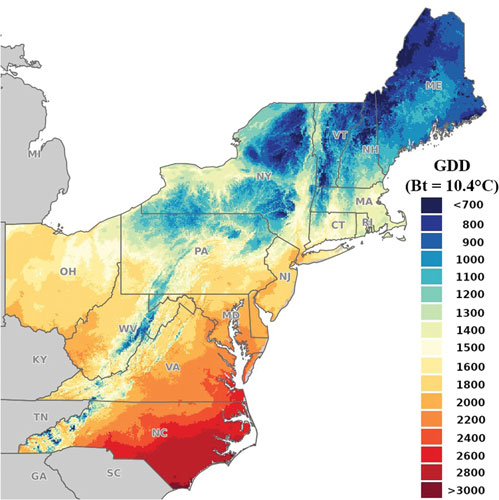

“Thus, since the northern, higher elevation in the Northern Appalachians, Catskills, Adirondacks, Green and White Mountains and the Allegheny Plateau region do not accumulate enough ADD for 1 percent adult emergence, these areas may have a very low risk of SLF population establishment,” according to the study.

Most of Maine, highland and lowland, is marginal for SLF reproduction. Other areas that do not provide enough season length to reach the adult stage include high elevations in the Appalachian Mountains of North Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia and Pennsylvania and the Northern Allegheny Plateau in Pennsylvania.

The location they chose for their investigation of the SLF’s seasonal activity — on red maple and tree-of-heaven host trees — was a housing development in Wyomissing, Pa., and the adjacent woodland. The 1.5-inch-long insect was first detected nearby in Berks County, Pa., in 2014. It has now expanded its range to at least 14 states. The study site has similar climate to that of its range in China, where natural foes control it.

Using roughly 51 degrees Fahrenheit as a lower threshold of development, the researchers related key life stage activity periods to the day of the year and ADD, starting Jan. 1, 2023 They came up with mathematical equations for nymphal instar, adult, and fall egg-mass deposition activity. Another set of mathematical equations was engineered for adult and fall egg-mass deposition periods using the first observation of adults as a starting date. With these equations, they estimated the geographic range where SLF can potentially complete a partial or full life cycle, from spring egg hatch to fall egg-mass deposition.

Where temperatures do (and don’t) suit SLF

Not surprisingly, the impact of both latitude and altitude seems to have a major effect on potential SLF expansion, as average temperature decreases with increases in altitude or latitude. Beyond that, the fact that altitude can offset the impact of latitude can have profound implication on SLF habitat, the researchers explain: “In the north, the Hudson, Connecticut, Delaware, Merrimack and Susquehanna River valleys and the area between the Catskills and Adirondacks Mountains, where the Erie Canal ran, are lower elevation and have longer season lengths than the surrounding area. In very short distances, the seasonal ADD can drop by 500 or more.”

SLF threaten crops such as almonds, apples, blueberries, cherries, peaches, grapes and hops, as well as hardwoods such as oak, walnut, and poplar. Typical of plant hoppers, they chew into stems and branches of plants to suck out sap, causing wilting, leaf curling and dieback. To make matters worse, like aphids, the SLF excretes sugary honeydew that attracts bees and wasps and feeds the growth of black sooty mold, which discolors and weakens plants and also makes a mess on patio furniture, cars, and anything else on which it grows. The honeydew problem is accelerated when SLF congregate, as they commonly do.

As the SLF continues to expand its range in the eastern U.S., a new study on the temperatures it needs for progressing through its life cycle offers a clearer picture of where the spotted lanternfly is likely to thrive — and where it’s not. Image: Dr. Dennis Calvin, Environmental Entomology

Dr. Calvin said that the equations developed may make a big difference in SLF control.

“It is hoped that, by having equations that can be used to predict the timing of key life-stage activity periods, pest managers can use this information to better time monitoring, surveillance. and control activities. It can save time and money by giving a smaller window to time these activities and also show how the timing of these activities varies across geographic locations,” Dr. Calvin said in the release.

More clues for SLF management

The Penn State scientists also turned up hints of other aspects of SLF behavior that, down the road, could boost control measures. Early in the season, the dominant sex of SLF on red maples was male. As fall and the reproductive season approached, however, females began to show up on the maples and then laid their eggs. The significance of egg laying close to the autumnal equinox suggests that its timing is not driven solely by DDs. Rather, it’s possibly also influenced by another environmental signal such as day length that allows the insect to determine the season is drawing to an end.

Co-author Dr. Julie Urban, also of Penn State, said that “the movement of adults that we report could potentially have implications for the monitoring that is done at satellite or ‘pop-up’ populations of SLF found in previously uninfested areas.” In other words, monitoring should be extended beyond the initial site of infestation and host species.

Leave A Comment