Illustration: Rob Dobi

Business is a game. Many believe it is an art, some believe it’s a science. But let’s look at the characteristics of gamesmanship. Games include competitive play, and a set of rules decided by skill, strength or luck. In football, we accumulate our score several different ways, such as a touchdown, field goal, extra point or safety. In business, our ultimate score is determined by profits, supported by cash flow, with the final prize being company valuation.

As a student of the game of running pest management businesses for the past 30 years, I have observed several areas of evolution in terms of building profitable and valuable companies. The winning game plan that has evolved, while nothing new, has become more refined, tweaked, taught and practiced at the most successful pest management companies.

The strength and beauty of our game has been the catalyst for the high valuations over the past several years, as well as for industry outsiders who have taken a strong interest in our industry. (See sidebar from my colleague Tim Mulrooney, a stock market analyst who covers the pest control industry at the investment bank William Blair & Co. Tim and I collaborate on a monthly Pest Index that tracks industry growth. It is used by institutional investors to determine their appetite for investment in our industry.)

In the early stages of building a pest management company, some factors can be at odds with one another. For example, one may sacrifice profitability by investing heavily in advertising to build a larger book of recurring services, which helps to increase company valuation. Or one may take a $100,000 bird job that provides a terrific profit, but because it is a one-time service and most likely won’t recur, it adds little to the company valuation. How about performing services and giving a customer lengthy credit terms? This move adds to accrual-based profit, but puts a strain on cash flow.

What if we could build a pest management company that maximizes profit, cash flow and value through the lessons my colleagues and I have learned over many years at our firms,

PCO Bookkeepers and PCO M&A Specialists?

If you are interested in these insights, read on. Here I present three case studies that illustrate concepts and initiatives you can implement to build a high-profit, high-valued firm.

CASE STUDY 1: How one pest control company tripled its cash flow by moving clients to monthly electronic payments?

Over the past several years, there has been a trend in our industry to charge customers’ credit cards prior to services. One of our clients at PCO Bookkeepers has taken this trend to a new level of cash flow expediency. This client worked with PCO Bookkeepers to implement a customer payment policy that removes seasonality from a seasonal business, accelerates cash flow and disassociates payments from service, which reduces the need for issuing customer credits when skipping services.

Our client’s signature service has three tiered options, each offering quarterly visits:

- Platinum: General pest control (GPC) plus a termite baiting system.

- Gold: GPC plus termite monitors; if termites are discovered, the customer receives a reduced price for treatment.

- Silver: GPC-only.

Remove seasonality from a seasonal business

The service is provided quarterly. However, the bill is charged via three equal monthly credit card charges or automated clearing house (ACH) drafts executed on the first day of each month of the quarter. The beauty of creating this subscription is that cash flow is pretty even across each month. It removes the lopsidedness that often occurs when quarterly cycles aren’t evenly distributed.

When cash flow follows seasonality, it makes planning difficult for paying bills and making payroll. In fact, many companies that have not figured out how to remove seasonality from their business cycles need to line up short-term credit lines, incurring interest charges. They also often have to explain seasonality to bankers when applying for such credit lines. Monthly subscription billing reduces exposure to these types of issues.

Accelerate cash flow

Cash flow — the movement of cash in and out of a business — is the lifeline of a company. It can be measured in amount and/or velocity. Vendor payments and payroll payments are dictated by terms and pay dates, but only can be adhered to if there is enough cash coming into the business.

Using a monthly subscription model helps ensure there is enough cash coming into the business to meet these obligations. Prior to adopting this new customer payment program, our client carried accounts receivable usually in the amount of 30 days of sales, as collection terms were 30 days. So, for example, if the client had annual revenue of $3.6 million, 30 days of sales would be $300,000 in receivables at any one time. Now the accounts receivable amount is almost zero, and cash flow is almost $300,000 higher.

Great idea? Yes, but there are some costs. Remember, the company is billing the customer three times as often as it was before the monthly subscriptions. This can triple the amount of collection exceptions, such as expired credit cards, declined credit cards for other reasons and insufficient funds on ACHs. While this method creates more reconciling issues, it reduces the amount of bills that need to be sent out. Now, there is no need to send each customer a bill. The monthly subscription amount is automatically billed and paid. It works just like your gym membership.

All in all, this reduction in accounts receivable adds to cash flow and helps a company meet financial obligations in time.

Disassociating payments from service

Using a subscription method also creates a situation where one is guaranteeing pest-free environments for customers, as opposed to charging a fixed amount for each service. In this model, one doesn’t need to worry about skips and re-treats on accounts because there are no credits issued for skips. However, customers can call for re-treats without an extra charge. Perhaps more important, one subliminally trains customers that they are not paying for a technician to come out and service their property; they are paying for pest-free environments. We find that when customers more holistically understand what they are actually paying for, they tend to value the service more, which ultimately can lead to higher retention rates.

CASE STUDY 2: How one company added more than $2 million to its bottom line by moving from monthly to quarterly service

This is a call for anyone who still provides monthly residential service to rethink the strategy and consider quarterly or triannual service. We met our client several years ago when his firm was producing $8 million in annual revenue, but losing close to $1 million per year.

The company’s signature offering was a residential monthly service priced at $50 to $60 per visit. Each service took about 30 minutes to provide. So, looking at the average dollars per hour, it was at about $120, a decent hourly rate where the company should be able to make a profit, right? The problem was that average travel time between stops was about 20 minutes. In an eight-hour day, each truck could produce nine or 10 stops, yielding $500 to $600.

Before I describe what PCO Bookkeepers prescribed for this ailing company, let’s look at some of the numbers. Assuming residential technician labor should be 21.7 percent (see PCO Bookkeepers’ “Pest Control Industry Cost Study” at pcobookkeepers.com/profitability), that means the company’s technicians would be making $108.50 to $130.20 per day, or $13.56 to $16.27 per hour. These rates are about a decade behind industry labor trends. If you assume an average technician is making $20 per hour, that drives the technician labor rate up to 26.6 percent to 32 percent, as opposed to the target of 21.7 percent.

You can do this analysis with each of the components of the direct cost basket on your profit-and-loss (P&L) statements (chemicals, vehicles, uniforms, etc.). For every point you increase your direct costs, you drop your gross profit by a point, thereby increasing your breakeven point. (Learn more about breakeven analysis at pcobookkeepers.com/focus-on-gross-margins-for-profitability).

In the case of our client, at his company’s volume, his pricing wasn’t even enough for the firm to break even. The company was grossing $8 million and losing money, so what do we do?

Those of you who follow my monthly columns in PMP know I say gross margins in the pest control industry need to be 50 percent to 55 percent, so we needed to elevate his gross margins to this level. There are a couple of ways we could have done that. We could have suggested paying his technicians less, which probably would not go well. Or we could increase his revenue per hour. In fact, we could create a win-win with customers while increasing his return per hour.

Enter quarterly service. If the company has customers paying $60 per month, would they be willing to pay $120 per quarter for an offering that includes one service and free re-treats? What does this method do for the daily yield per truck? We determined it doubled the daily yield per truck, leaving the cost of labor the same and catapulting the company’s gross margin.

Ultimately, moving to quarterly services is precisely what we did. The result? The company went from losing close to $1 million per year to making over $1 million a year. It sounds easy, and it is.

Plus, since technicians only visit a customer once per quarter (plus retreats) rather than monthly, we’ve freed up a lot of technician labor hours. These additional hours can be used to sell more business without adding technicians, to reduce overtime and/or perhaps part ways with marginal technicians.

One thing to beware of are re-treats: They need to be closely monitored, especially as the number of treatments are reduced. However, in aggregate over the entire customer base, if technicians are trained properly, re-treats do not detract from this strategy.

So how does our client like his “new company”? Well, he now is considering moving to triannual service. This type of program is the most profitable we see clients offer.

CASE STUDY 3: Why a firm with stronger recurring revenue is less risky and ultimately worth more?

We’ve all heard it before: You build a strong and valuable pest management business by building a base of customers who purchase your service on a subscription basis, which gives you, the business owner, a strong base of recurring revenue. There’s nothing new here, but let’s explore why the recurring revenue model is so powerful.

We’ve all heard it before: You build a strong and valuable pest management business by building a base of customers who purchase your service on a subscription basis, which gives you, the business owner, a strong base of recurring revenue. There’s nothing new here, but let’s explore why the recurring revenue model is so powerful.

Businesses with recurring revenue provide less risk, exposure to the weather, the economy and day-to-day events that may interrupt business cycles. The stability of recurring revenue allows steady growth and predictable cash flow. When we talk about best-in-class pest management companies and relate it back to valuations, those with the highest recurring to non-recurring revenue ratios, generally are the most valuable.

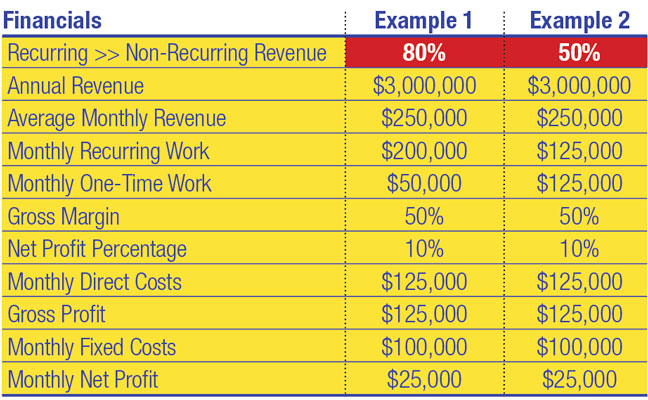

To prove the point, let’s look at two example companies with the following make up:

Both companies are identical in revenue, gross margin, fixed costs and monthly profit. The only difference is Example 1’s revenue is made up of 80 percent recurring revenue, while Example 2’s recurring revenue is only 50 percent. When all is good, their financial performances are exactly the same.

What happens when we get a major jolt to the economy? Consider a seasonal slowdown, a financial meltdown (a la the Great Recession of 2008), a major geopolitical event (9/11), or how about one that was unthinkable a few years ago: a pandemic that would shut down the country. What happens is that one-time job revenue dries up, as well as some recurring revenue.

What happens when we get a major jolt to the economy? Consider a seasonal slowdown, a financial meltdown (a la the Great Recession of 2008), a major geopolitical event (9/11), or how about one that was unthinkable a few years ago: a pandemic that would shut down the country. What happens is that one-time job revenue dries up, as well as some recurring revenue.

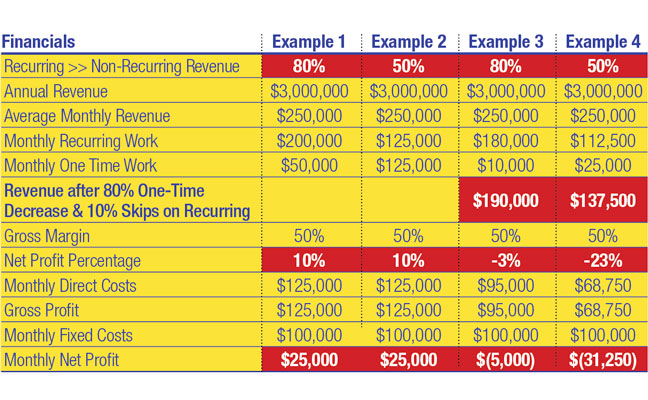

Let’s take the above examples and add some assumptions. Let’s assume that a pandemic happens, and the government shuts down the economy. Well, thank goodness pest control is deemed an “essential service.” However, citizens get scared and curtail purchasing decisions until there is more clarity in the economy. As a result, assume that 80 percent of one-time revenue dries up, and we incur a 10 percent skip rate on recurring revenue.

Example 3 is what happens to Example 1 (the 80 percent recurring revenue company) when we apply the assumptions above. Example 3 shows that our recurring revenue drops 10 percent from $200,000 to $180,000 — a $20,000 reduction in revenue. Our one-time revenue drops 80 percent, from $50,000 to $10,000, which is a $40,000 reduction in revenue. Together, we’ve lost $60,000 in monthly revenue. This takes us from a $25,000 monthly net profit to a $5,000 monthly net loss.

Example 4 is what happens to Example 2 (the 50 percent recurring revenue company) when we apply the assumptions above. Example 4 shows that our recurring revenue drops 10 percent from $125,000 to $112,000, a $12,500 reduction in revenue. Our one-time revenue drops 80 percent from $125,000 to $25,000 (a $100,000 reduction in revenue). Together, we’ve lost $112,500 in monthly revenue. This takes us from a $25,000 monthly net profit to a $31,250 monthly net loss.

With a $5,000 monthly loss, we can hold on and see how things turnaround and what moves we can make to ensure survival. But with a $31,250 monthly hit, we can ill afford to sustain this type of loss for long, before we end up in real trouble or bankruptcy court.

Why are there very different results for two companies that, prior to the pandemic, seemed to have all the same characteristics except their recurring to non-recurring revenue ratio? It has to do with: a) the loss of revenue; and b) the cost structure of how a service company operates. Examples 1 and 3 had a 24 percent reduction in revenue. Examples 2 and 4 had a 45 percent reduction in revenue. And while direct costs could immediately be reduced in proportion to the loss of revenue, each company had $100,000 of fixed costs that could not be reduced on the turn of a dime. The result was that fixed costs remained constant no matter how big the revenue reduction, making the loss in Examples 2 and 4 a total calamity.

While this illustration seems extreme, Examples 2 and 4 were real examples of a client that PCO M&A Specialists (sellmypcobusiness.com) was working on to sell in early 2020. Needless to say, the deal got put on ice. The good news is that in hindsight, our industry wasn’t hurt as much as restaurants, bars and bowling alleys, but we definitely took a two-month hit at the end of Q1 and the beginning of Q2 2020. Luckily, our client has restructured his business, is on the mend and will get a deal done after all.

As you can see, not only does a higher percentage of recurring to non-recurring revenue provide stability and predictability when building a pest management firm, it also reduces risk. For these reasons, the firm with the higher ratio also garners a higher valuation.

Leave A Comment